Whether or not you agree with the premise in that title, I’m afraid I can’t take the credit – or the blame. That’s because I’m just quoting the headline of one of a series of full-page ads in the Wall Street Journal last year from the large information security company Tanium.

But, indeed…

WHY IS CYBERSECURITY GETTING WORSE?”

Other ads in the series offered an answer:

WE WILL SPEND $160B THIS YEAR ON SECURITY SOLUTIONS THAT ARE FAILING TO PROTECT US. IT’S BECAUSE THE CURRENT APPROACH IS FLAWED.

In the year and a half since the ads ran, that figure has grown to nearly $200 billion.

Spending on security technology is rapidly increasing.

That is, spending on defective security technology is rapidly increasing.

How can that be?

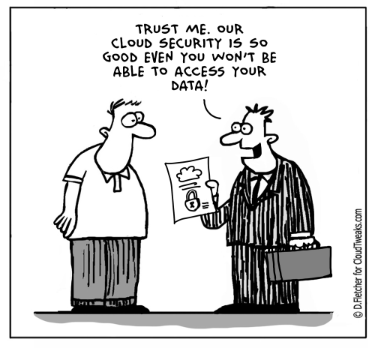

The disturbing answer is that security technology is what we call a WTI. A “wrinkle treatment industry” is one that thrives as long as its products don’t work.

That may sound nefarious, but the road to security hell was paved with good intentions. Those of us who walked that road got off on the wrong foot quite innocently in the seventies.

Managers at the time tended to understand that security in their offices was about accountability; it wasn’t about a cops-and-robbers game of chasing bad guys. For example, instead of asking their office building lobby receptionist to determine whether visitors had good or bad intentions, they had them ask visitors for a form of ID and the name of the person they were to meet with. Again, real security is about accountability.

But those same experienced managers were intimidated by their newfangled computers. Urged by IBM to start building security into their IT systems, they asked their young programmers (like me) to give them guidance on security. Since our twenty year olds’ notion of security was all about what we saw on cop shows, cybersecurity got started on the assumption that it’s all about catching bad guys. Of course that means that it’s based on the assumption that it’s possible to determine the intentions and character of the sender just by looking at a stream of bits.

In fact, that is almost always impossible. And while it’s easy for the hacker to change IP addresses and other cues about the origin of a stream of bits, each time they do that causes an arduous start-over process for the defender. It’s an easy win for the attacker and a lose-lose strategy for the defender.

(But for the vendors of security products it means steadily increasing revenue – a rather big win for them.)

Exacerbating the problem is a fact of marketing life. As every copywriter knows, advertising must touch an emotion in order to be effective. Images of guard dogs and razor wire and soldiers carrying automatic weapons evoke emotions. Images of office building lobbies and ID badges, not so much. Cops-and-robbers security messages get a prospect’s attention, while accountability, like so many other things in life, is so effective that it doesn’t call attention to itself.

Yet CISOs and COOs and CEOs have so much invested in their solutions, which are such an integral part of their operations, that stepping back and confronting the nakedness of the security emperor would simply be too disruptive to the challenging task of managing the company’s information infrastructure.

Real security is about accountability. It’s not about trying to determine the intentions and character of the sender of a stream of bits.

That means that real security starts with identity. Oddly, the name that’s been adopted for the turn toward identity is zero trust. In other words, start by not trusting the identity of the user.

That begs the question: “Then what?” Obviously, accountability requires a level of trust in the identity claim of the user. The vulnerabilities of username – password systems are as well covered in the media as are the calls for passwordlessness. Yet passwords hang on like, well, cops-and-robbers security.

Identity certificates and their associated PENs (personal endorsement numbers, a form of PKI private key) are the solution. They should be deployed not only for an organization’s own employees but employees of suppliers and distributors and for that matter outside contractors.

For users of a company’s website who seek to establish an account relationship, we can look forward to the day when universal identity certificates, issued by duly constituted public authority, are pervasive. Until then it’s a matter of ad hoc identity verification, which means performing a verification each time a new user shows up. That’s not only costly, but easily subverted by hackers.

However we get to measurably reliable identity certificates, accountability is the basis of real security. You might ask “If PKI identity certificates, and PKI in general, are so good, why aren’t they in use everywhere?

Here are twelve reasons behind the misunderstandings, resistance, and slow adoption of this powerful solution:

Reason one: You can’t have a working PKI without both public keys and private keys. But the very term “Public Key Infrastructure” covers the specifications for public keys only, leaving the specs for private keys “as an exercise for the reader.” It’s like providing a car whose engine compartment contains only a notice saying “find a suitable engine and install it here.”

Reason two: PKI terminology can be bizarre!

True – the terminology has been carelessly used and badly fuddled. Of all the gobbledygook in information technology, the mangling of the term CERTIFICATE has been among the worst! “Knowledgeable PKI experts will say things like “sign the document with your certificate” – while knowing that the signature is made by the private key, not the certificate! As a result, people who might be interested in putting PKI to work have become confused and discouraged.

Reason three: The conventional wisdom is that PKI is brilliant but too complex for practical deployment.

Translation: PKI is more about non-technology than about technology. Its principal “moving part” is a human being. That makes it “complex” to technologists.

Complex things are all around us, having been made to fit with real life, with the complexity buried behind friendly interfaces. We are surrounded by technologies whose design incorporates their human user. PKI has avoided that.

Reason four: Reliable identities of users – necessary for effective PKI – have been scarce.

Reason five: Attempts at reliable PKI identity have not adequately protected users’ privacy.

Reason six: PKI has conveyed authenticity without requiring a legitimate source of authenticity. When the term “certification authority” was coined, it was defined as “any entity that is able to operate a CA server.” The consequence of that was illustrated when StartCom, a commercial certification authority that was noted for its diligence in verifying the claims of its certification subjects, as sold to WoSign, whose purpose was to issue fraudulent certificates.

The phrase “commercial certification authority” makes as much sense as “commercial vital records department” or “commercial city hall.” A CA cannot be something that can be bought and sold, and certificates cannot be a commodity that’s sold like Cabbage Patch Doll “birth certificates.” A CA must represent DCPA: Duly Constituted Public Authority.

Reason seven: PKI deployments have tried to replace signatures of people with signatures of objects. That doesn’t work.PKI must be built upon identity certificates of human beings, not digital objects. The notion of an accountable object is folly. To serve that intent, the object’s claim must be digitally signed using the private key of an identity certificate. The object’s certificate is just an extension of its responsible party’s certificate, ie the real certificate.

Reason eight: The role of encryption in PKI is confusing.

People who are not involved with asymmetric cryptography tend to think of PKI as an encryption/decryption tool, as it does involve encryption and decryption. But its purpose is to establish authenticity by way of accountability, binding an identifiable human being to their actions.

To further confuse things, the asymmetric key pair is often used to control access to and use of a symmetric key, which is what is really used in the encryption and decryption of useful-sized files.

This is just one of those places where something that is inherently confusing needs to be explained as well and as frequently as possible. Changing the word used to identify the asymmetric pair from “keys” to “numbers” will help. Leave the word “key” to symmetric processes.

Reason nine: Most security technologies are built on an old, fundamentally flawed assumption from the 1960s and 1970s. The flawed assumption is that it is possible to determine the intention and character of the sender of a stream of bits by thoroughly examining it. Until very recently, this “catch the bad guys” mentality has drawn attention away from the real solution, which is about accountability, and which in turn is established by means of true digital signatures everywhere.

“Zero Trust” is a half step toward security built on accountability rather than a cops-and-robbers game.

To illustrate the complete move to accountability we have found success with an office building receptionist metaphor, asking an audience whether they would direct their building’s lobby receptionist to identify visitors with bad intentions rather than asking for identity documents in order to establish a measure of accountability.

Reason ten: PKI, when done right, works TOO well!

Companies have become very comfortable and happy with their easy access to personal information. PKI identity certificates may be used by the subjects of the information to control its use. That’s poses a threat to the revenue models of companies that treat stolen personally identifiable information as their own money-making balance sheet asset.

Reason eleven: The assumption has been that PKI’s inherent complexity calls for it to be implemented within one organization, running that organization’s certification authority for internal use only.

In fact, a public PKI with a CA that represents duly constituted public authority reduces the complexity of deployment and administration.

To illustrate, imagine a company that chooses to base its employee IDs on company-generated birth certificates rather than birth certificates issued by the vital records department of a public authority. Terminating employees would need their birth certificates revoked, and new employees would need to go through a costly and bureaucratic process for gathering EOI, or Evidence of Identity.

Reason twelve: When PKI was first conceived, the required computing power to handle even 512 bit key pairs would strain the capabilities of the processors of the day. Now of course each of us has a supercomputer in our pocket, which doesn’t even work up a sweat doing2048 bit asymmetric cryptography.

To sum up, the impediments to common adoption of PKI may be categorized as implementation flaws, perception barriers, and establishment pushback.

- For the implementation flaws, we can migrate to PKI done right.

- For problems of perception, we plan video-based education and outreach.

- For establishment pushback, we’re taking the lead in a paradigm shift to a new era of real security, and real privacy.

PKI has been around for almost half a century. Must we wait until security problems get so bad that the only economic sector that remains in the black is the cops-and-robbers security vendor sector?

Or will we move to accountability-based security?

Zero trust is a faltering half step in that direction.

Let’s go the rest of the way with PKI – done right!

By Wes Kussmaul