Today, I am publishing the Distributed Computing Manifesto, a canonical

document from the early days of Amazon that transformed the architecture

of Amazon’s ecommerce platform. It highlights the challenges we were

facing at the end of the 20th century, and hints at where we were

headed.

When it comes to the ecommerce side of Amazon, architectural information

was rarely shared with the public. So, when I was invited by Amazon in

2004 to give a talk about my distributed systems research, I almost

didn’t go. I was thinking: web servers and a database, how hard can

that be? But I’m happy that I did, because what I encountered blew my

mind. The scale and diversity of their operation was unlike anything I

had ever seen, Amazon’s architecture was at least a decade ahead of what

I had encountered at other companies. It was more than just a

high-performance website, we are talking about everything from

high-volume transaction processing to machine learning, security,

robotics, binning millions of products – anything that you could find

in a distributed systems textbook was happening at Amazon, and it was

happening at unbelievable scale. When they offered me a job, I couldn’t

resist. Now, after almost 18 years as their CTO, I am still blown away

on a daily basis by the inventiveness of our engineers and the systems

they have built.

To invent and simplify

A continuous challenge when operating at unparalleled scale, when you

are decades ahead of anyone else, and growing by an order of magnitude

every few years, is that there is no textbook you can rely on, nor is

there any commercial software you can buy. It meant that Amazon’s

engineers had to invent their way into the future. And with every few

orders of magnitude of growth the current architecture would start to

show cracks in reliability and performance, and engineers would start to

spend more time with virtual duct tape and WD40 than building

new innovative products. At each of these inflection points, engineers

would invent their way into a new architectural structure to be ready

for the next orders of magnitude growth. Architectures that nobody had

built before.

Over the next two decades, Amazon would move from a monolith to a

service-oriented architecture, to microservices, then to microservices

running over a shared infrastructure platform. All of this was being

done before terms like service-oriented architecture existed. Along

the way we learned a lot of lessons about operating at internet scale.

During my keynote at AWS

re:Invent

in a couple of weeks, I plan to talk about how the concepts in this document

started to shaped what we see in microservices and event driven

architectures. Also, in the coming months, I will write a series of

posts that dive deep into specific sections of the Distributed Computing

Manifesto.

A very brief history of system architecture at Amazon

Before we go deep into the weeds of Amazon’s architectural history, it

helps to understand a little bit about where we were 25 years ago.

Amazon was moving at a rapid pace, building and launching products every

few months, innovations that we take for granted today: 1-click buying,

self-service ordering, instant refunds, recommendations, similarities,

search-inside-the-book, associates selling, and third-party products.

The list goes on. And these were just the customer-facing innovations,

we’re not even scratching the surface of what was happening behind the

scenes.

Amazon started off with a traditional two-tier architecture: a

monolithic, stateless application

(Obidos) that was

used to serve pages and a whole battery of databases that grew with

every new set of product categories, products inside those categories,

customers, and countries that Amazon launched in. These databases were a

shared resource, and eventually became the bottleneck for the pace that

we wanted to innovate.

Back in 1998, a collective of senior Amazon

engineers started to lay the groundwork for a radical overhaul of

Amazon’s architecture to support the next generation of customer centric

innovation. A core point was separating the presentation layer, business

logic and data, while ensuring that reliability, scale, performance and

security met an incredibly high bar and keeping costs under control.

Their proposal was called the Distributed Computing Manifesto.

I am sharing this now to give you a glimpse at how advanced the thinking

of Amazon’s engineering team was in the late nineties. They consistently

invented themselves out of trouble, scaling a monolith into what we

would now call a service-oriented architecture, which was necessary to

support the rapid innovation that has become synonymous with Amazon. One

of our Leadership Principles is to invent and simplify – our

engineers really live by that moto.

Things change…

One thing to keep in mind as you read this document is that it

represents the thinking of almost 25 years ago. We have come a long way

since — our business requirements have evolved and our systems have

changed significantly. You may read things that sound unbelievably

simple or common, you may read things that you disagree with, but in the

late nineties these ideas were transformative. I hope you enjoy reading

it as much as I still do.

The full text of the Distributed Computing Manifesto is available below.

You can also view it as a PDF.

Created: May 24, 1998

Revised: July 10, 1998

Background

It is clear that we need to create and implement a new architecture if

Amazon’s processing is to scale to the point where it can support ten

times our current order volume. The question is, what form should the

new architecture take and how do we move towards realizing it?

Our current two-tier, client-server architecture is one that is

essentially data bound. The applications that run the business access

the database directly and have knowledge of the data model embedded in

them. This means that there is a very tight coupling between the

applications and the data model, and data model changes have to be

accompanied by application changes even if functionality remains the

same. This approach does not scale well and makes distributing and

segregating processing based on where data is located difficult since

the applications are sensitive to the interdependent relationships

between data elements.

Key Concepts

There are two key concepts in the new architecture we are proposing to

address the shortcomings of the current system. The first, is to move

toward a service-based model and the second, is to shift our processing

so that it more closely models a workflow approach. This paper does not

address what specific technology should be used to implement the new

architecture. This should only be determined when we have determined

that the new architecture is something that will meet our requirements

and we embark on implementing it.

Service-based model

We propose moving towards a three-tier architecture where presentation

(client), business logic and data are separated. This has also been

called a service-based architecture. The applications (clients) would no

longer be able to access the database directly, but only through a

well-defined interface that encapsulates the business logic required to

perform the function. This means that the client is no longer dependent

on the underlying data structure or even where the data is located. The

interface between the business logic (in the service) and the database

can change without impacting the client since the client interacts with

the service though its own interface. Similarly, the client interface

can evolve without impacting the interaction of the service and the

underlying database.

Services, in combination with workflow, will have to provide both

synchronous and asynchronous methods. Synchronous methods would likely

be applied to operations for which the response is immediate, such as

adding a customer or looking up vendor information. However, other

operations that are asynchronous in nature will not provide immediate

response. An example of this is invoking a service to pass a workflow

element onto the next processing node in the chain. The requestor does

not expect the results back immediately, just an indication that the

workflow element was successfully queued. However, the requestor may be

interested in receiving the results of the request back eventually. To

facilitate this, the service has to provide a mechanism whereby the

requestor can receive the results of an asynchronous request. There are

a couple of models for this, polling or callback. In the callback model

the requestor passes the address of a routine to invoke when the request

completed. This approach is used most commonly when the time between the

request and a reply is relatively short. A significant disadvantage of

the callback approach is that the requestor may no longer be active when

the request has completed making the callback address invalid. The

polling model, however, suffers from the overhead required to

periodically check if a request has completed. The polling model is the

one that will likely be the most useful for interaction with

asynchronous services.

There are several important implications that have to be considered as

we move toward a service-based model.

The first is that we will have to adopt a much more disciplined approach

to software engineering. Currently much of our database access is ad hoc

with a proliferation of Perl scripts that to a very real extent run our

business. Moving to a service-based architecture will require that

direct client access to the database be phased out over a period of

time. Without this, we cannot even hope to realize the benefits of a

three-tier architecture, such as data-location transparency and the

ability to evolve the data model, without negatively impacting clients.

The specification, design and development of services and their

interfaces is not something that should occur in a haphazard fashion. It

has to be carefully coordinated so that we do not end up with the same

tangled proliferation we currently have. The bottom line is that to

successfully move to a service-based model, we have to adopt better

software engineering practices and chart out a course that allows us to

move in this direction while still providing our “customers” with the

access to business data on which they rely.

A second implication of a service-based approach, which is related to

the first, is the significant mindset shift that will be required of all

software developers. Our current mindset is data-centric, and when we

model a business requirement, we do so using a data-centric approach.

Our solutions involve making the database table or column changes to

implement the solution and we embed the data model within the accessing

application. The service-based approach will require us to break the

solution to business requirements into at least two pieces. The first

piece is the modeling of the relationship between data elements just as

we always have. This includes the data model and the business rules that

will be enforced in the service(s) that interact with the data. However,

the second piece is something we have never done before, which is

designing the interface between the client and the service so that the

underlying data model is not exposed to or relied upon by the client.

This relates back strongly to the software engineering issues discussed

above.

Workflow-based Model and Data Domaining

Amazon’s business is well suited to a workflow-based processing model.

We already have an “order pipeline” that is acted upon by various

business processes from the time a customer order is placed to the time

it is shipped out the door. Much of our processing is already

workflow-oriented, albeit the workflow “elements” are static, residing

principally in a single database. An example of our current workflow

model is the progression of customer_orders through the system. The

condition attribute on each customer_order dictates the next activity in

the workflow. However, the current database workflow model will not

scale well because processing is being performed against a central

instance. As the amount of work increases (a larger number of orders per

unit time), the amount of processing against the central instance will

increase to a point where it is no longer sustainable. A solution to

this is to distribute the workflow processing so that it can be

offloaded from the central instance. Implementing this requires that

workflow elements like customer_orders would move between business

processing (“nodes”) that could be located on separate machines.

Instead of processes coming to the data, the data would travel to the

process. This means that each workflow element would require all of the

information required for the next node in the workflow to act upon it.

This concept is the same as one used in message-oriented middleware

where units of work are represented as messages shunted from one node

(business process) to another.

An issue with workflow is how it is directed. Does each processing node

have the autonomy to redirect the workflow element to the next node

based on embedded business rules (autonomous) or should there be some

sort of workflow coordinator that handles the transfer of work between

nodes (directed)? To illustrate the difference, consider a node that

performs credit card charges. Does it have the built-in “intelligence”

to refer orders that succeeded to the next processing node in the order

pipeline and shunt those that failed to some other node for exception

processing? Or is the credit card charging node considered to be a

service that can be invoked from anywhere and which returns its results

to the requestor? In this case, the requestor would be responsible for

dealing with failure conditions and determining what the next node in

the processing is for successful and failed requests. A major advantage

of the directed workflow model is its flexibility. The workflow

processing nodes that it moves work between are interchangeable building

blocks that can be used in different combinations and for different

purposes. Some processing lends itself very well to the directed model,

for instance credit card charge processing since it may be invoked in

different contexts. On a grander scale, DC processing considered as a

single logical process benefits from the directed model. The DC would

accept customer orders to process and return the results (shipment,

exception conditions, etc.) to whatever gave it the work to perform. On

the other hand, certain processes would benefit from the autonomous

model if their interaction with adjacent processing is fixed and not

likely to change. An example of this is that multi-book shipments always

go from picklist to rebin.

The distributed workflow approach has several advantages. One of these

is that a business process such as fulfilling an order can easily be

modeled to improve scalability. For instance, if charging a credit card

becomes a bottleneck, additional charging nodes can be added without

impacting the workflow model. Another advantage is that a node along the

workflow path does not necessarily have to depend on accessing remote

databases to operate on a workflow element. This means that certain

processing can continue when other pieces of the workflow system (like

databases) are unavailable, improving the overall availability of the

system.

However, there are some drawbacks to the message-based distributed

workflow model. A database-centric model, where every process accesses

the same central data store, allows data changes to be propagated

quickly and efficiently through the system. For instance, if a customer

wants to change the credit-card number being used for his order because

the one he initially specified has expired or was declined, this can be

done easily and the change would be instantly represented everywhere in

the system. In a message-based workflow model, this becomes more

complicated. The design of the workflow has to accommodate the fact that

some of the underlying data may change while a workflow element is

making its way from one end of the system to the other. Furthermore,

with classic queue-based workflow it is more difficult to determine the

state of any particular workflow element. To overcome this, mechanisms

have to be created that allow state transitions to be recorded for the

benefit of outside processes without impacting the availability and

autonomy of the workflow process. These issues make correct initial

design much more important than in a monolithic system, and speak back

to the software engineering practices discussed elsewhere.

The workflow model applies to data that is transient in our system and

undergoes well-defined state changes. However, there is another class of

data that does not lend itself to a workflow approach. This class of

data is largely persistent and does not change with the same frequency

or predictability as workflow data. In our case this data is describing

customers, vendors and our catalog. It is important that this data be

highly available and that we maintain the relationships between these

data (such as knowing what addresses are associated with a customer).

The idea of creating data domains allows us to split up this class of

data according to its relationship with other data. For instance, all

data pertaining to customers would make up one domain, all data about

vendors another and all data about our catalog a third. This allows us

to create services by which clients interact with the various data

domains and opens up the possibility of replicating domain data so that

it is closer to its consumer. An example of this would be replicating

the customer data domain to the U.K. and Germany so that customer

service organizations could operate off of a local data store and not be

dependent on the availability of a single instance of the data. The

service interfaces to the data would be identical but the copy of the

domain they access would be different. Creating data domains and the

service interfaces to access them is an important element in separating

the client from knowledge of the internal structure and location of the

data.

Applying the Concepts

DC processing lends itself well as an example of the application of the

workflow and data domaining concepts discussed above. Data flow through

the DC falls into three distinct categories. The first is that which is

well suited to sequential queue processing. An example of this is the

received_items queue filled in by vreceive. The second category is that

data which should reside in a data domain either because of its

persistence or the requirement that it be widely available. Inventory

information (bin_items) falls into this category, as it is required both

in the DC and by other business functions like sourcing and customer

support. The third category of data fits neither the queuing nor the

domaining model very well. This class of data is transient and only

required locally (within the DC). It is not well suited to sequential

queue processing, however, since it is operated upon in aggregate. An

example of this is the data required to generate picklists. A batch of

customer shipments has to accumulate so that picklist has enough

information to print out picks according to shipment method, etc. Once

the picklist processing is done, the shipments go on to the next stop in

their workflow. The holding areas for this third type of data are called

aggregation queues since they exhibit the properties of both queues

and database tables.

Tracking State Changes

The ability for outside processes to be able to track the movement and

change of state of a workflow element through the system is imperative.

In the case of DC processing, customer service and other functions need

to be able to determine where a customer order or shipment is in the

pipeline. The mechanism that we propose using is one where certain nodes

along the workflow insert a row into some centralized database instance

to indicate the current state of the workflow element being processed.

This kind of information will be useful not only for tracking where

something is in the workflow but it also provides important insight into

the workings and inefficiencies in our order pipeline. The state

information would only be kept in the production database while the

customer order is active. Once fulfilled, the state change information

would be moved to the data warehouse where it would be used for

historical analysis.

Making Changes to In-flight Workflow Elements

Workflow processing creates a data currency problem since workflow

elements contain all of the information required to move on to the next

workflow node. What if a customer wants to change the shipping address

for an order while the order is being processed? Currently, a CS

representative can change the shipping address in the customer_order

(provided it is before a pending_customer_shipment is created) since

both the order and customer data are located centrally. However, in a

workflow model the customer order will be somewhere else being processed

through various stages on the way to becoming a shipment to a customer.

To affect a change to an in-flight workflow element, there has to be a

mechanism for propagating attribute changes. A publish and subscribe

model is one method for doing this. To implement the P&S model,

workflow-processing nodes would subscribe to receive notification of

certain events or exceptions. Attribute changes would constitute one

class of events. To change the address for an in-flight order, a message

indicating the order and the changed attribute would be sent to all

processing nodes that subscribed for that particular event.

Additionally, a state change row would be inserted in the tracking table

indicating that an attribute change was requested. If one of the nodes

was able to affect the attribute change it would insert another row in

the state change table to indicate that it had made the change to the

order. This mechanism means that there will be a permanent record of

attribute change events and whether they were applied.

Another variation on the P&S model is one where a workflow coordinator,

instead of a workflow-processing node, affects changes to in-flight

workflow elements instead of a workflow-processing node. As with the

mechanism described above, the workflow coordinators would subscribe to

receive notification of events or exceptions and apply those to the

applicable workflow elements as it processes them.

Applying changes to in-flight workflow elements synchronously is an

alternative to the asynchronous propagation of change requests. This has

the benefit of giving the originator of the change request instant

feedback about whether the change was affected or not. However, this

model requires that all nodes in the workflow be available to process

the change synchronously, and should be used only for changes where it

is acceptable for the request to fail due to temporary unavailability.

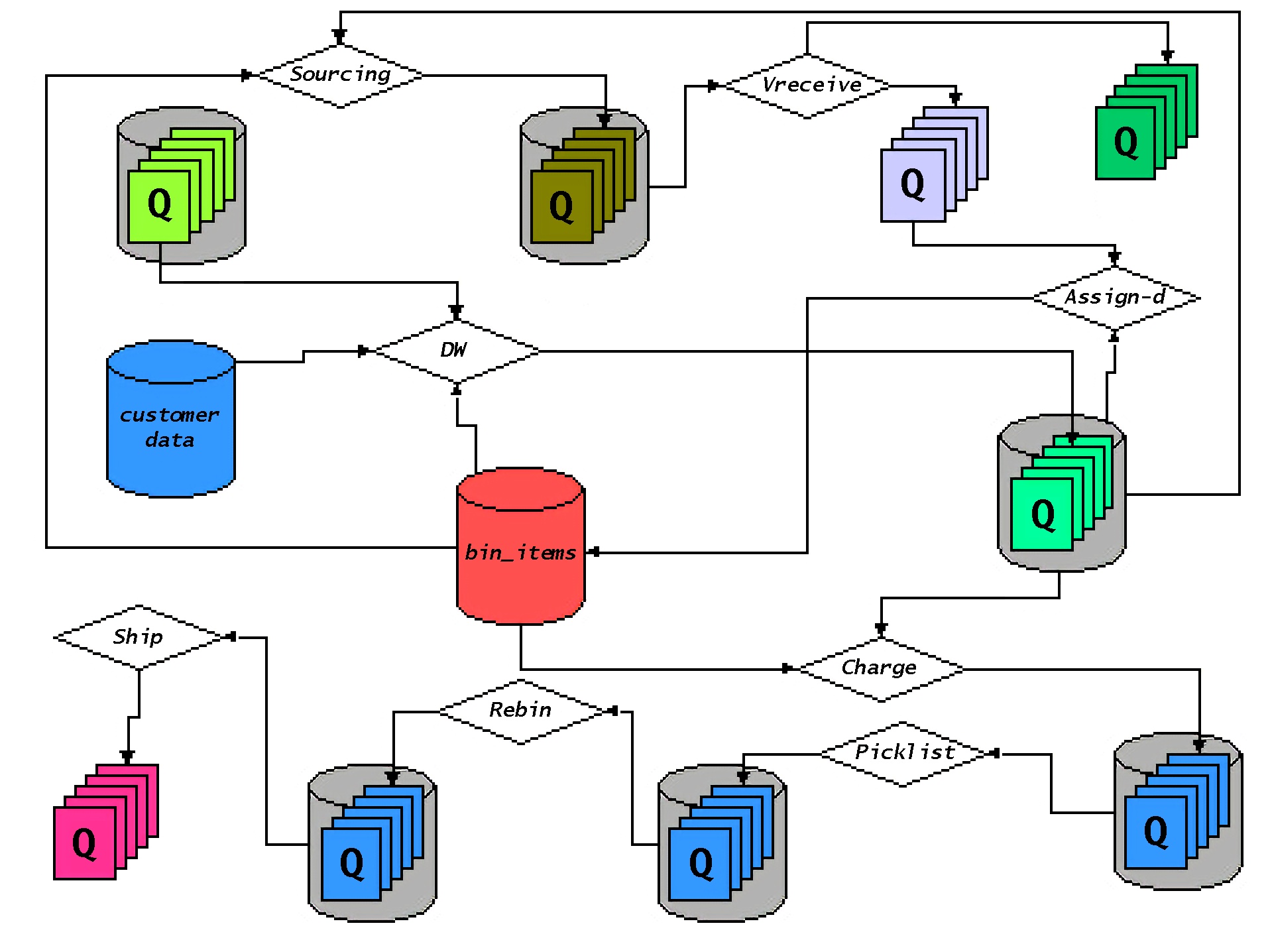

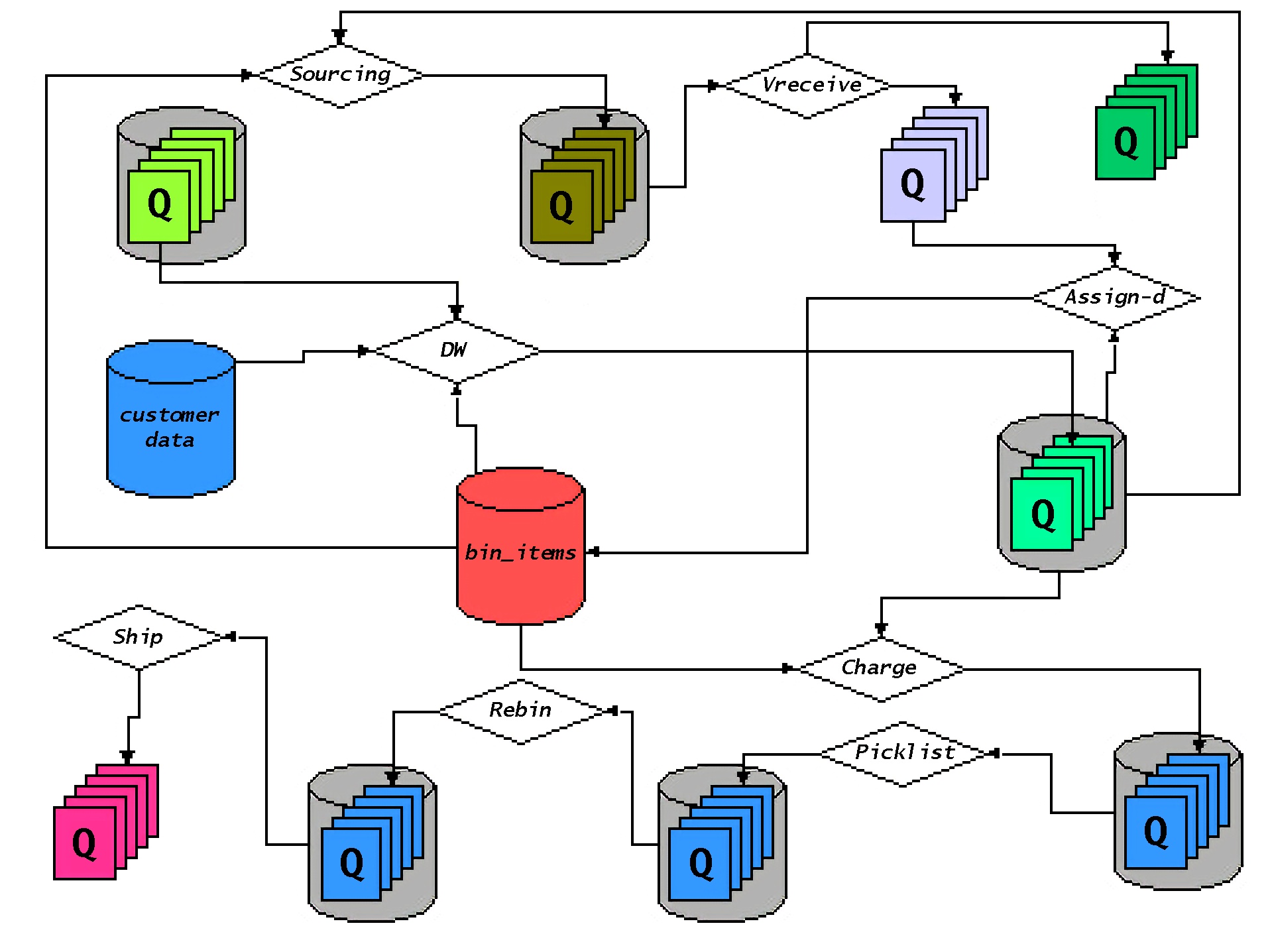

Workflow and DC Customer Order Processing

The diagram below represents a simplified view of how a customer

order moved through various workflow stages in the DC. This is modeled

largely after the way things currently work with some changes to

represent how things will work as the result of DC isolation. In this

picture, instead of a customer order or a customer shipment remaining in

a static database table, they are physically moved between workflow

processing nodes represented by the diamond-shaped boxes. From the

diagram, you can see that DC processing employs data domains (for

customer and inventory information), true queue (for received items and

distributor shipments) as well as aggregation queues (for charge

processing, picklisting, etc.). Each queue exposes a service interface

through which a requestor can insert a workflow element to be processed

by the queue’s respective workflow-processing node. For instance,

orders that are ready to be charged would be inserted into the charge

service’s queue. Charge processing (which may be multiple physical

processes) would remove orders from the queue for processing and forward

them on to the next workflow node when done (or back to the requestor of

the charge service, depending on whether the coordinated or autonomous

workflow is used for the charge service).

© 1998, Amazon.com, Inc. or its affiliates.